An Interview with Nabil Ahmed

March 2018

Nabil Ahmed is the founder of INTERPRT, an independent project that investigates environmental crime using spatial analysis towards the adoption of ecocide as an international crime. The project is focused on gathering evidence on long term conflicts in the Pacific. He has written for art, science and architecture publications such as Third Text, Scientific Reports, Volume magazine and Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth (Sternberg, 2014). He holds a PhD from the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London where he is affiliated with Forensic Architecture. He is a senior lecturer at the Cass School of Architecture at London Metropolitan University.

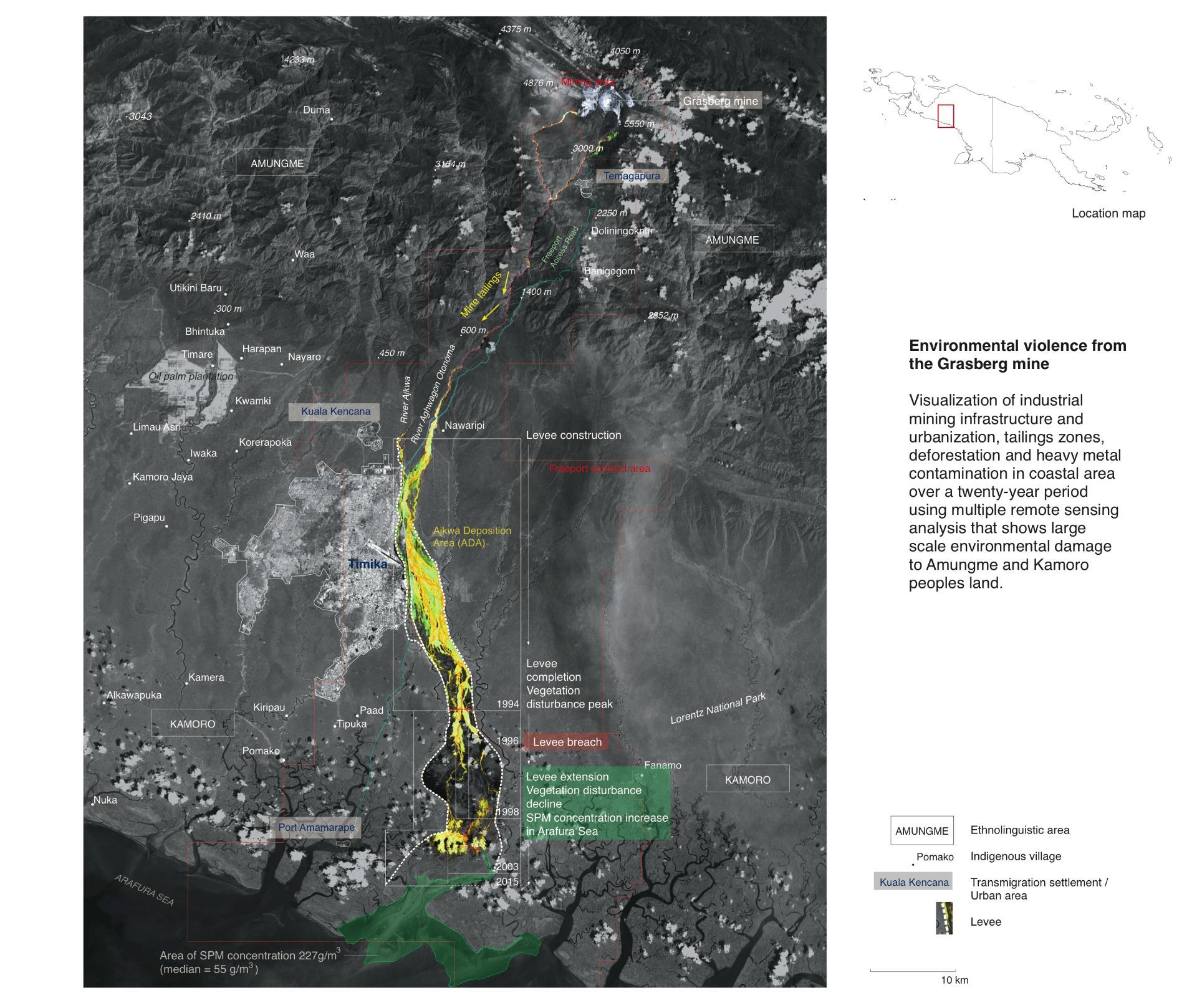

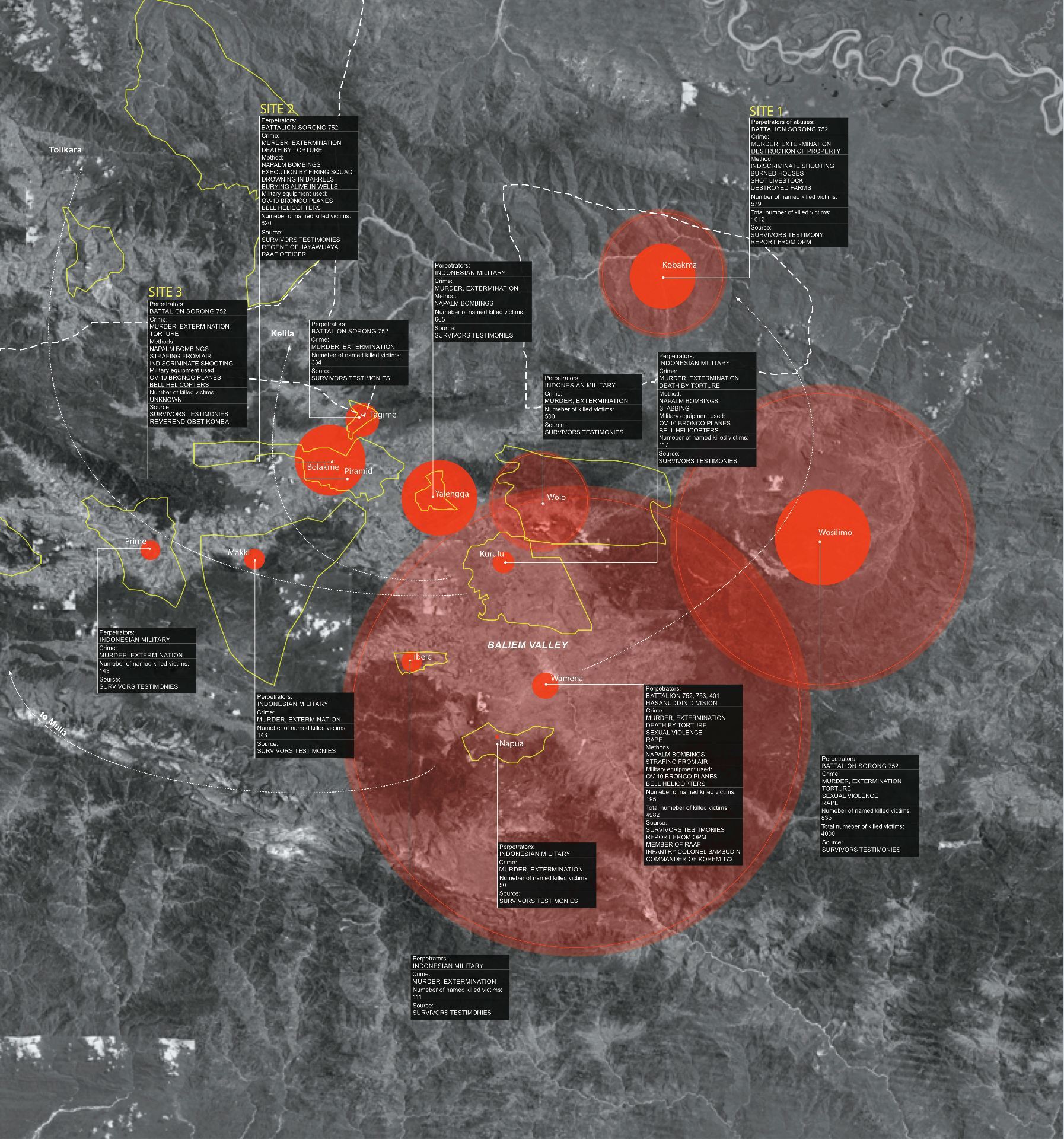

Located on the Western half of the island of New Guinea, West Papua is a militarized territory and the site of a long-term conflict between Indonesia and indigenous Melanesian Papuan peoples seeking self-determination. Since 2013, Ahmed has investigated cases of “crimes against nature” or ecocide in the West Papua conflict, gathering spatial evidence that shows a malign interaction between state violence and ecological destruction stemming from corporate greed. The investigation is organized around three sites: Indonesian military campaigns of mass killings of Papuans in the central highlands, landscape history of contamination from the Grasberg gold and copper mine in Mimika, and more contemporary land grabs and forest fires in the Merauke region that together make the case for deliberate destruction of Papuan social, cultural and natural environments.

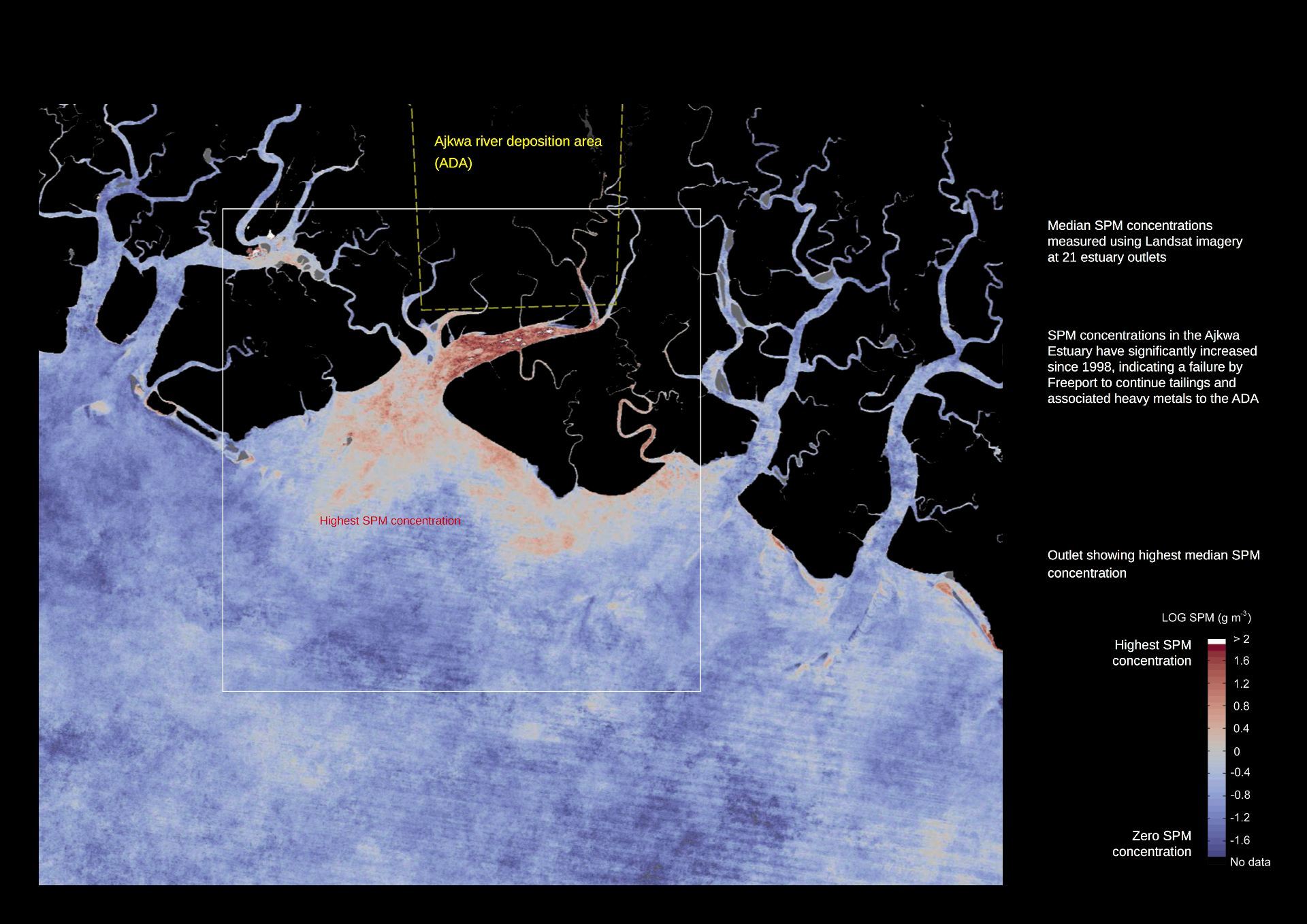

Nabil Ahmed, Remote sensing analysis of contamination from Grasberg mine, West Papua. SPM refers to suspended particulate matter, often with reference to pollution (finely divided solids or liquids dispersed through the air from combustion processes, industrial activities or natural sources).

T. J. Demos: Can you describe what the “Inter-Pacific Ring Tribunal” (INTERPRT) is exactly, who is involved besides yourself, and when it was formed?

Nabil Ahmed: INTERPRT is a research and design project for the investigation of environmental crimes, namely ecocide in the Pacific. It’s an interdisciplinary project involving spatial designers, researchers and lawyers. Ecocide is not yet recognized as an international crime under the Rome Statute, the body of law which gives mandate to the International Criminal Court (ICC). We want to help in the process of developing ecocide law. In the twentieth century the Pacific and Oceania was the site where major nuclear tests took place. Today Pacific small island states are at the frontiers of climate change due to sea level rise. Along the Pacific ring are major conflicts around mining. The project uses the geological line of the Pacific ring as a diagram linking the region’s environmental histories of decolonization and militarization to its current ecological crises. We began working on the West Papua conflict and are now beginning to look at a number of other specific cases. The project is also interested in conceiving alternative forums such as hearings and mock trials in support of Pacific centred communities and depending on where investigations lead. We are working with International Foundation Baltasar Garzon (FIBGAR) and the ecocide law expert Polly Higgins in the campaign to introduce ecocide into the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

TJD: Why is the notion of “ecocide” important, in your view, and what hope is there currently for getting it recognized, and more importantly enforced, in international law? How does it correlate with the “rights of nature,” which enact an juridico-ontological shift in the status of the nonhuman by granting it legal standing?

NA: Justice begins by calling state and corporate environmental crimes by their true name: Ecocide or crimes against nature and humanity. The path of criminal justice is the only way for accountability to be realized, although there is no perfect forum. There is certainly intersectionality with the notion of ‘rights of nature’ though they are not the same. In order to claim nature as a victim of environmental crime it might be practical to frame nature as a subject of law, not only granting it an ontological right but rights as any other legal subject. But as far as I know rights of nature have not yet been put forward in an international criminal law context. Ecocide is not only a matter of international law, but an interaction between the domestic and the international (insofar as the ICC is a court of last resort); the principle is that if ecocide is made into international law, there would emerge a judicial culture to stop ecocide. So long as corporations can externalize fines (if it ever gets that far) for causing environmental harm, where not only nature is seen as a resource to be looted but also resulting environmental harm is seen in economic terms, irreparable damage to ecology and people’s livelihoods and cosmologies can be swallowed up in the most banal of evils, the balance sheet. But especially given that ecocide is not yet in international law but we know what ecocide is and who is responsible, profit-driven and widespread environmental destruction, land grabs, climate change etc. and that impacted communities are continuously resisting worldwide, the project is also interested in using the investigations as a way to organize, support and act as contingent platforms for trying ecocide cases in alternative forums (whether national or international) that are outside state-judicial institutions. This is necessary because there is a difference between law and what is actually practiced and how it’s implemented or not. There are gaps, and that’s the matter of politics, which must involve civil society at certain pressure points.

TJD: Looking at your maps of the Grasberg mine in West Papua, a major site of copper mining and environmental pollution and a primary hyperobject of your research, we see that they chart visual signs of environmental and state-military violence on the island. The mining operation releases, as you observe, highly toxic tailings of arsenic, cadmium, and selenium into the Otomina and Ajkwa Rivers, draining eventually into the Arafura Sea (between Papua and Australia), after traversing a path through highly sensitive biodiverse forests, which has generated longstanding Indigenous resistance, and related military repressions and human rights violations (particularly in the 1970s under the US-supported Suharto regime). Some have referred to it as a context of genocide. Can you describe how you came up with your visual methodology and how you see it as useful to the political struggle to protect Papuan Indigenous rights and land?

NA: We try to expose the startling scale of a long term, spatially diffused and ongoing violence around mining, state violence, deforestation and land grab. In Papua and elsewhere the landscape is no longer a background on which the violence takes place. For hard to reach places, satellite images can help show exactly where conflict is occuring. If environmental violence by its very nature is spatially diffused and has been going on for long periods of time, then spatial analysis becomes a useful tool for its visualization. Satellite images taken over time can also show how a conflict has developed and what was destroyed, where and how facts on the ground were created. We can also start to recognize patterns of destruction in how places are related. We can determine a systematic or structural approach on the part of perpetrators i.e. by establishing hot spots. In West Papua, the context of ‘genocide’ is not independent to ‘ecocide’. For example we visualized the Asian Human Rights Commission’s “Neglected Genocide”, a report detailing a series of human rights abuses that took place in the Central Highlands of Papua, during the military operations in 1977-1978. In this publication, the AHRC reports that at least 4,146 Papuans, including children, women, and the elderly were killed by the Indonesian military. Astonishingly the report names victims but does not show where these killings happened or point out their concentration in the Papuan highlands, along specific ethnic lines, which we attempted to address. Grasberg mine is located in the same mountainous landscape, which is still controlled by the Indonesian military. The analysis of the Grasberg mine and its environmental impacts was a collaboration with the remote sensing geographer Mike Alonzo (American University) and later Jamon Van den Hoek (Oregon State University). The transformation of Papuan landscape from mining is, in fact, a territorial transformation that is not only representative of a political conflict but is materially the conflict in motion registered on the soil, subsoil, water, people, plants and life – dispersed in the ecology of Papua over space and time.

TJD: How did you become interested in West Papua, a highly valuable geography for mining, palm oil plantations, fisheries and forestry under colonial-like control by Indonesia, even as Indigenous groups contest such politico-economic imposition?

NA: In West Papua, state violence is entangled with the geopolitics of extraction through settler-colonial power. The Indonesian state acts with total impunity. It’s capture—what you call ‘colonial-like’—by Indonesia was ironically part and parcel of the docolonizaiton process as Indonesia emerged as a fighting nation against Dutch imperialism. That takeover isn’t (only) about indigenous people versus state, colonial powers etc. but about how the international state system under the United Nations deprived a people of their right to self-determination. The undercurrent of these negotiations was the vast natural resource they saw in the territory. Indonesia practices a strategy of denial when it comes to anyone questioning its claim over West Papua. Powerful states will go to all lengths to enforce a narrative of denial. The many national and international companies that operate there take advantage of this denial and culture of impunity. Some years ago I was writing about the lethal arsenic poisoning of Munir Said Thalib, a leading Indonesian human rights activist by the Indonesian state, which was covered up. To this day justice has not been served. The poisoned body of the human rights defender led to West Papua, to a conflict where the poisoning was going on at a territorial scale.

TJD: In your 2015 essay “Land Rights: Counter-Mapping in West Papua,” you write: “New forms of eco-political and aesthetic practices are called for, to hold accountable those who profit from such violence and those in whom we place our trust for protection.” Who is profiting? And how will new forms of eco-political and aesthetic practices assist locals and internationals in justice campaigns?

NA: If we consider ecocide as one of the most serious crimes, then the doctrine of a “command responsibility” [the legal doctrine of hierarchical accountability for war crimes, referring to the duty to supervise subordinates, as established in the early twentieth-century] is instructive. No longer limited to war time offenses but corporate activities in peacetime, that hierarchy of responsibility includes those individuals with the authority to issue orders, to plan and commit environmental crimes. But the very definition of impunity is a total lack of justice and that’s where we are working from. Looking closely at the material transformation of landscapes of extractive violence is part of an aesthetic practice. Spatial analysis is an aesthetic practice and is one of many ways of reading landscapes. A calculus of social and human costs is marked on extraction landscapes. Such an aesthetic practice is then also bringing to the table new and alternative narratives to old conflicts. But it has to be done tactically.

TJD: Papua is geographically distant from the perspective of Europe and the US, yet Freeport mining has had a major stake in the Grasberg Mine in West Papua since the 1960s and has its headquarters in Phoenix, New Mexico in the US. Can you discuss how your practice might lead toward political shifts not only in the Indonesian context, but also necessary ones in the US? How might your work support a politics of relational geographies?

NA: The way I understand it, it’s not only distant geography that makes it a difficult place to report from, but also its political reality on the ground (restricted access to journalists, UN etc.) makes it a difficult place to access. The conflict is also ongoing, although not all-out-war anymore but much more low intensity. It’s also a longterm conflict which, according to many Indonesians I spoke to, is not well known in Indonesia. The shift, which I am interested in, is actually a pivot to the Pacific, and it’s a strategic one shared by the (self-determination) movement. While there are hundreds of ethnic groups on the island of New Guinea (including PNG across the border in the east), broadly speaking Papuans are Melanesian people, and the island is therefore part of Oceania. Within the political self-determination movement it’s therefore crucial to frame the West Papua conflict as a Pacific conflict and not only a southeast Asian one, or an Indonesian one. And it’s some of the small island Pacific states such as Vanuatu (also Melenasian) that are supporting the Papuan struggle. Freeport, the mining company that is often associated with Grasberg where it owns the majority share is indeed headquartered in the U.S. but it is also a transnational company and its reach is also transnational. INTERPRT is interested in holding state and corporate environmental crime to account using accurate, fact-based spatial analysis. Our work therefore might support a culture of emerging transnational investigative practice.

TJD: It might be argued that people in developed countries are implicated in this and other similar geopolitical conflicts, as all benefit in one way or another from the technologies and consumer goods that depend on, and provide the demand for extraction. Can there be solidarity between the environmentally-concerned and Indigenous Papuans? If so, how to address, and not erase, the differential levels of complicity, even with those who are politically active? Is this an issue in your work?

NA: The privilege of consumers and users of technology are shared across class lines as much as they are between developed and underdeveloped countries. Although I would argue that people in many developed countries have equally benefited from colonialism. The way to change the continued demand for extraction requires a change in the economic system, as we would agree, namely commodity capitalism. What will this take? One avenue might be the criminalization of state and corporate environmental crime. While consumers are complicit, as I mentioned earlier, it’s the producers, enablers and profiteers that must first be held accountable. While we can’t wish away the presence of a world of inequality and asymmetry, we can work towards a project of its transformation. The public knowledge of the Papuan conflict has often focused on basic human rights violations and not on the centrality of environmental harm over the self-determination question. We are working with International Lawyers for West Papua (ILWP), a group of lawyers that address the Papuan conflict using international law, on this point. Before solidarity the environmentally-concerned needs to recognize conflicts in ecological terms.

TJD: In the same piece I mentioned earlier you write: “As a political act, [the] aim to ‘appropriate the state’s techniques and manner of representation’ has its danger in that fixing indigenous spatial knowledge into maps that follows standardized geospatial protocols can become stratified in the state cartographic project, the very powers it seeks to contest.” How do you avoid this prospect in your practice?

NA: This was written particularly in reference to participatory mapping in Indonesia as practiced by some NGOs and indigenous organizations towards marking out customary land boundaries in order to combat state-sponsored land grabbing. Before taking a critical stance, it’s important to acknowledge such practices. I was referring to the fact that the claim gets complicated when participatory maps could be appropriated by the state just as indigenous cultures have been appropriated. Information, let’s say about previously ‘empty’ spaces, such as through the location of ancestral trees or everyday practice, because they adhere to global location systems, would be forever fixed and ‘legible’ by the state for planning purposes. At the same time Cartesian maps have been widely used as a contemporary territorial strategy, so why shouldn’t any group use them, indigenous or otherwise? I think such contestations are productive. We are not representing hidden knowledge or any specific cultural identities as such but leveraging publicly available data to fight environmental crime.

TJD: To produce your imagery and counter-mapping project, you draw on fairly new visual technologies, including geospatial data, GIS, remote sensing and satellite imagery, only recently analyzed critically in visual culture studies. These have also been used, as you point out, by the extraction industry as early as the 1970s in the Indonesian context, when such visual technologies became available on the commercial markets following their exclusive military applications. How do you liberate such approaches from their neocolonial associations?

NA: Spatial data and its analysis has of course been critically examined for a long time by spatial disciplines such as geography and architecture yet their application in monitoring and reporting on conflict, human rights violations and environmental disasters by the spatial disciplines is much more recent. I think it’s interesting that these are now being looked at by visual culture. Perhaps you will agree, but this also has to do with a shift of representation of conflicts, human rights violations, etc., when NGOs such as Amnesty routinely use (basic) satellite imagery it enters the public consciousness. I should also mention resolution of commercial satellites is far higher and prohibitively expensive to acquire. What is freely available is of much lower resolution provided by institutions such as NASA’s longstanding LANDSAT and European Space Agency’s (ESA) SENTINEL satellites for scientific use. I’m not sure whether the use of satellite data by non-academic environmental groups or activists was part of the brief. Perhaps short of building alternative satellites, this itself is quite liberating.

TJD: Can you discuss how your work attempts to connect the differential epistemologies of “the sky and the ground,” remote sensing science and indigenous agency/knowledge? Where are the connections, where the tensions?

NA: The relation between the sky and the ground might be one of scale. Precisely because it’s about scale it doesn’t mean large is abstract and small is concrete. On the contrary it expands the object of the dispute. Having said that, I am particularly referring to what in remote sensing is called ‘ground truth’ which relates the satellite imagery of a particular place to the ground. In other words it refers to gathering of data in the field to help interpret and validate remotely recorded data. On gathering ground truth data for the spatial analysis of the environmental damage caused by industrial mining in West Papua, we have worked with members of LEMASA, the Amungme people’s tribal council. Grasberg mine is located in their ancestral land. The mining concession area is militarized and access is restricted so local knowledge was crucial.

TJD: How does your project collaborate, correlate, and compare with the counter-cartography work of the Network for Participatory Mapping (JKPP) and the Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN), which use local spatial knowledge to support Indigenous land-rights claims?

NA: As I wrote about the work of these two organizations in the same article you refer to earlier, it’s important to note that as far as I know, these organizations are active in the Indonesian archipelago around land rights claims, and not in occupied West Papua. While land rights in response to systematic land grab is an operative concept, the work we are doing gathers spatial evidence on the conflict in West Papua where the context is totally different than the the rest of the archipelago, but only comparable to conflict in East Timor and possibly Aceh, which is about self-determination. Some of the participatory maps made by indigenous organizations and NGOs have also been submitted to the Indonesia geospatial agency for inclusion, which accepts state sovereignty as a fact. My point was that the same tactic in West Papua might reinforce the territory as a province, thereby weakening its self-determination claims.

TJD: If mapping can act as a form of “local territorialization”—as Nancy Peluso argues—according to which cartographic visuality operates as well as an advocacy tool for native land rights, how do you situate your own agency and practice as a non-Papuan within this geopolitical context?

NA: Local territorialization is first a method of establishing control of a given territory by the state. Yet its exploitation is a process that exceeds and moves across national boundaries. In the case of impunity and ecocide in West Papua, it is a moral imperative and a political responsibility to support new possibilities of action regardless where the crime occurs.

In December 2017, INTERPRT participated in the 16th Session of the Assembly of State Parties (ASP) of the International Criminal Court (ICC) at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, as part of an informal coalition of Pacific states, the NGO Institute for Environmental Security and international lawyers led by British attorney Polly Higgins towards the campaign to introduce ecocide as an international crime. INTERPRT’s exhibition for the ASP/ICC forum, “Ecocide in West Papua,” was blocked by the Indonesian state at the UN, given the nature of the evidence we were to present. The proposed exhibition was produced and supported by our informal coalition in collaboration with ILWP and other Papua focused groups, including AwasMIFEE and the filmmakers collective Papuan Voices. This demonstrated the potential of our project for international justice, as recognized through the pushback of a powerful state, the world’s fifth largest emitter of Greenhouse gases.