- What remains of a politico-cultural horizon beyond contemporary capitalism? Is the term “revolution” appropriate today? Why or why not?

It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.― Assata Shakur

In 2012 we asked John Holloway a similar set of questions in Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy. Holloway’s response:

In 2012 we asked John Holloway a similar set of questions in Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy. Holloway’s response:

The difficulty is that we cannot be sure what a revolution looks like. The concept that dominated in the last century, that of taking state power and then transforming society, did not work and in some cases led to horrendous results. We have to separate the idea of revolution from that of taking state power. Revolutionary change is more urgent than ever, but it is not through capturing state power that we can bring it about.

I find it helpful to think in terms of three of the Zapatista sayings. First (of course) ¡Ya basta! Enough! We have reached the limit of what we will accept. We cannot think of a future revolution, revolution must be here and now. In the cracks we assume here and now our responsibility for the world. It cannot be a question of incremental change through reforms which may improve situations but do nothing to break the capitalist dynamic of destruction. Break, break now, break by living the world we want to create. Secondly, preguntando caminamos: Asking we walk. We walk asking because we do not know the way and also because asking-discussing is a process of collective determination, and collective determination is the way. Thirdly, caminamos, no corremos, porque vamos muy lejos: We walk, we do not run, because we are going very far. This is not postponement, quite the contrary.

There is a reversal of the traditional temporalities of revolution. The old idea was of revolution in the future, which would then change things dramatically. Now we think rather of rupture here and now (with a resounding crack!) which opens the arduous and often slow process of creating a different world, always pushing against-and-beyond that which exists. So: a Tidal wave of ruptures, growing to the point where capitalism is swept aside.

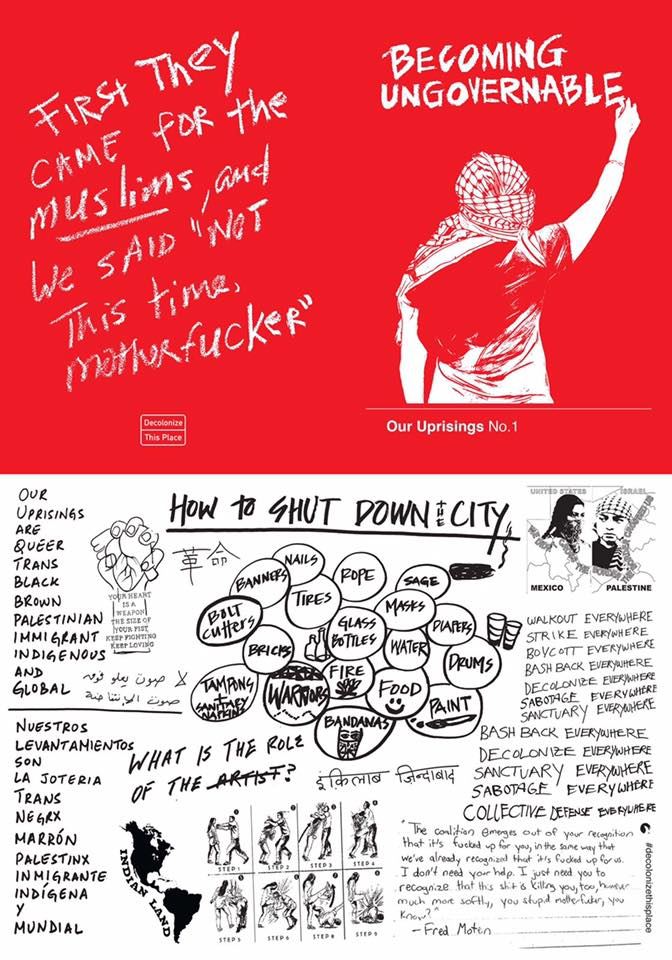

If we couple this beginning of a response by Holloway with learning from the failures of Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter and #NoDAPL, we can imagine moving away from silo-ed struggles and social justice frameworks to resisting and building in all the ways imaginable within a framework of decolonization, whereby we understand that settler colonialism is a structure not an event, that capitalism is part and parcel of Western hegemony and coloniality, and that the solutions and responses cannot come from the same epistemology and way of doing things that has got us to this brink. Abolish White Supremacy! Dismantle Patriarchy! #DecolonizeThisPlace

- Where does the Revolution exist in contemporary cultural politics, if it exists at all?

We prefer verbs like “decolonize” and “unsettle” as a practice of living, thinking and doing, doing while thinking, and in the process blurring the lines between art and activism, culture and politics, organizing and aesthetics, and moving towards de-occupying spaces, exercising epistemic disobedience, rearranging relations, challenging power to create space for imagination.

An example of this approach exists in NYC in Decolonize This Place. Decolonize This Place, which formed in 2016 by MTL and a few others (as “MTL+”), built on the experiences and movement-generated theory produced recently to deepen solidarity, foster shared analysis, and produce formations that allow groups to retain the specificities of our struggles in coalition while moving together and separately towards decolonial freedom.

In the evolution of the movement to Decolonize This Place, an action-oriented space was established in Manhattan. The space was rooted in five strands of struggle to inform the political and cultural work to be done: indigenous struggle, black liberation, free Palestine, global wage workers, and de-gentrification. Activities included but were not limited to a series of talks, workshops, screenings, meetings, and direct actions that seeks to 'liberate art from itself...not to end art, but to unleash its powers of direct action and radical imagination', and begin by creating a space that de-centers whiteness.

Decolonize This Place facilitated not only to mobilize artists, cultural workers, organizers, activists, educators, and members of the community to struggle for justice through direct action and organizing, art and culture, resisting and building, while bridging different movements to learn, work, and support with one another.

Collaborators of Decolonize This Place include:

Aida Youth Center—Palestine

American Indian Community House

Black Poets Speak Out

Black Lives Matter - PRATT

Black Youth Project 100

Bronx Not For Sale

Brooklyn Anti-Gentrification Network

Chinatown Arts Brigade

Comité Boricua En La Diáspora

Common Practice New York

Direct Action Front for Palestine

Eagle and Condor Community House

El Salón

Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F.)

Hyperallergic

Insurgent Poets Society

Justice for Akai Gurley Family

Jive Poetic

Mahina Movement

NYC Shut It Down

NYC Stands for Standing Rock

NYC Students for Justice in Palestine

Queens Anti-Gentrification Network

Take Back The Bronx

Tidal: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy

Wing On Wo & Co.

Woman Writers Of Color

and more...

- What new meanings or manifestations might revolution take on in the post- or neo-colonial present, one threatened with ecological as well as politico-economic and military catastrophe?

These questions lead to a dead end in terms of an answer and solutions, largely because our starting point should not be what kind of “revolution” we need to deal with where we are today (for reasons already mentioned above). We should instead begin by thinking how these structures of oppression are maintained? How are we complicit? What are we willing to give up in the context of struggle? What is the “we” and what kind of coalition and how are we building it in the process of struggle?

The coalition emerges out of your recognition that it’s fucked up for you, in the same way that we’ve already recognized that it’s fucked up for us. I don’t need your help. I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker, you know?

― Fred Moten, quoted in the “Introduction” to The Undercommons.

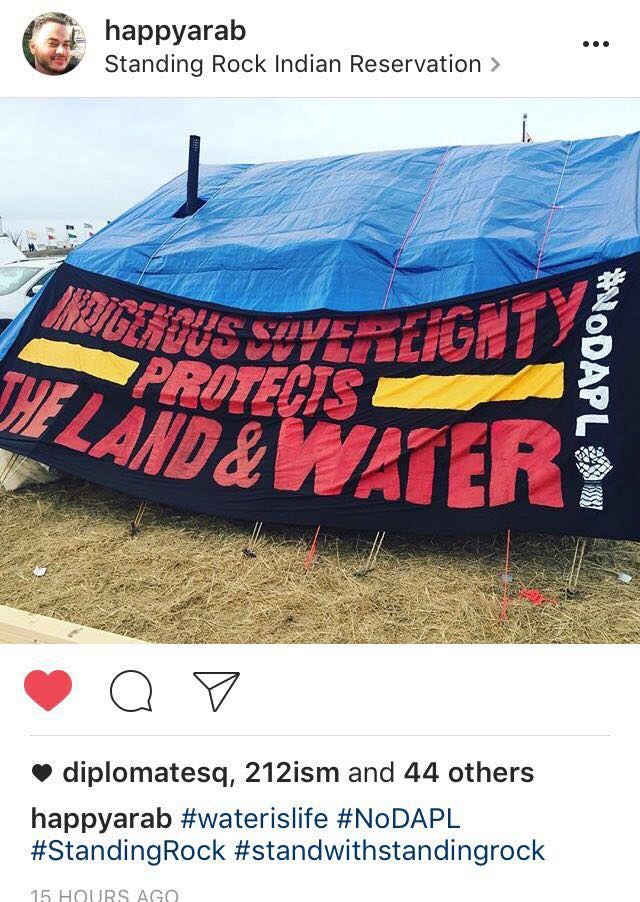

This becomes relevant when we reflect on the climate justice movement, and most recently, for example, in regards to the Climate March in New York or certain groups that went to Standing Rock in solidarity during #NoDAPL. Their tactics and strategies, framing and analysis, and overall rhetoric perpetuates settler colonization. It also ignores the debts owed to indigenous peoples on this land who continue to be rendered invisible and vulnerable by the full force of the state. The resistance at Standing Rock is a reminder of centuries of struggle for sovereignty over land, water and air, which continues to this day.

- Is there hope for political transformation within the terms of actually existing representative democracy? Is it possible to address climate change adequately within the terms of capitalism?

No.

- What do art, aesthetic action, and visual culture have to offer when it comes to the imperatives of political transformation? What role might they have, more broadly, in building and envisioning political transformation?

There is a war in the imagination and we are losing. We should urgently ask, and be honest with ourselves, “How are we living?” and then, despite a deep feeling of helplessness, still act. As MTL Collective, we are engaged in a practice in which the artist’s work does not add only an artistic flair to this or that campaign, but rather contributes research and organizing, aesthetics and action, theory and debriefing and analysis—this entire dialectical process is the art practice. Today, the artist is an organizer, recognizes capitalism has always been hostile to human and non-human life, and understands that people fight where they are.

Gulf Labor, and its direct-action wing, Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F.); NYC Stands with Standing Rock; Black Youth Project 100; Insurgent Poets Society; Direct Action Front for Palestine; Chinatown Art Brigade; and Decolonize This Place are all varied examples of such a practice. They take aim at a range of targets: labor exploitation, settler colonialism, white supremacy, the capture of public space, climate colonization, gentrification, police violence, Israeli settler colonialism, rape and sexual assault, and more. Yet, they do not work in silos. They take action in New York City while making connections among one another as well as to other geographies and struggles.

So what if, as artists and cultural producers, when we speak of “art” and “activism”, we put both under erasure? What if we strike art to liberate it from itself? Not to end art, but to free it from the circuits of capital, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and debt, and to unleash its powers to imagine that which is not immediately apparent. And, what if, as we reject the specialization of activism we choose a never ending process of experimentation and questioning, or, we choose, as the Zapatistas say, to “make the path by walking.” Let art be training in the practice of decolonial freedom.

- How might different subjects—whether differently abled, aged, or particularly vulnerable and precarious—be unevenly affected by the prospect of revolution/political transformation? What work is being done, or needs to be done, to ensure that radical transformation is radically inclusive?

For this question we refer to Jasbir Puar. In a recent article titled, Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!, Jasbir talks about her newly released book, The Right to Maim and why it does not seek to answer the question where is our disability pride movement?, stating:

“Instead, it hopes to change the conversation to one that challenges the presumption that the distinction between who is disabled and who is not should fuel a pride movement. I explore if and how this binary effaces the biopolitical production of precarity and (un)livability that runs across these identities. The project, then, is not just one that hopes to contribute to intersectional movement building, though let me insist that this is crucial from the outset. That is to say, Black Lives Matter and the struggle to end the Israeli occupation of Palestine are not only movements “allied” with disability rights, nor are they only distinct disability justice issues. Rather, I am motivated to think of these fierce organizing practices collectively as a disability justice movement itself, as a movement that is demanding an end to so many conditions of precaritization that debilitate many populations. At our current political conjuncture, Black Lives Matter, the Palestinian solidarity movement, the protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline to protect sacred grounds and access to water: these are some of the movements that are leading the way to demand livable lives for all. These movements may not represent the most appealing or desired versions of disability pride. But they are movements anchored, in fact, in the lived experiences of debilitation, implicitly contesting the right to maim, and imagining multiple futures where bodily capacities and debilities are embraced rather than weaponized.”

“Instead, it hopes to change the conversation to one that challenges the presumption that the distinction between who is disabled and who is not should fuel a pride movement. I explore if and how this binary effaces the biopolitical production of precarity and (un)livability that runs across these identities. The project, then, is not just one that hopes to contribute to intersectional movement building, though let me insist that this is crucial from the outset. That is to say, Black Lives Matter and the struggle to end the Israeli occupation of Palestine are not only movements “allied” with disability rights, nor are they only distinct disability justice issues. Rather, I am motivated to think of these fierce organizing practices collectively as a disability justice movement itself, as a movement that is demanding an end to so many conditions of precaritization that debilitate many populations. At our current political conjuncture, Black Lives Matter, the Palestinian solidarity movement, the protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline to protect sacred grounds and access to water: these are some of the movements that are leading the way to demand livable lives for all. These movements may not represent the most appealing or desired versions of disability pride. But they are movements anchored, in fact, in the lived experiences of debilitation, implicitly contesting the right to maim, and imagining multiple futures where bodily capacities and debilities are embraced rather than weaponized.”

- In our counter-factual, anti-regulatory, climate-change-denying era, how might the arts support scientific endeavors? How might the Sciences learn from art activism?

The problem to us seems the primacy of Western science over other knowledges and ways of being and living. Western science and research are complicit in furthering the project of domination by which Western modernity is inextricably linked with the present and ever evolving condition of coloniality. When we say “science” we should think whose epistemology is behind it? When we think of “art” we should think who came up with aesthetics? And, when we think of “activism” we should wonder how is it different from organizing, and would it not make sense that given the conditions we face today to think of them differently.

MTL is a collective based in New York that combines research, aesthetics and activism in its practice. It includes Nitasha Dhillon, an artist and organizer, and Amin Husain, a lawyer, artist, and organizer, both co-founders and co-editors of Tidal Occupy Theory magazine.