The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (John Jordan and Isa Fremeaux), April 13, 2016

1. How were you involved in art activism during the COP21?

The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii) was involved in a series of overlapping projects. Some of which fit more easily into the definition / genrefication of art activism, and others not so obviously. Seeing as at the Labofii we deal with all forms of resistance with an artistic approach, applying creativity to the forms as we would any art work and thinking narratively, aesthetically, theatrically etc., I will include all of the projects.

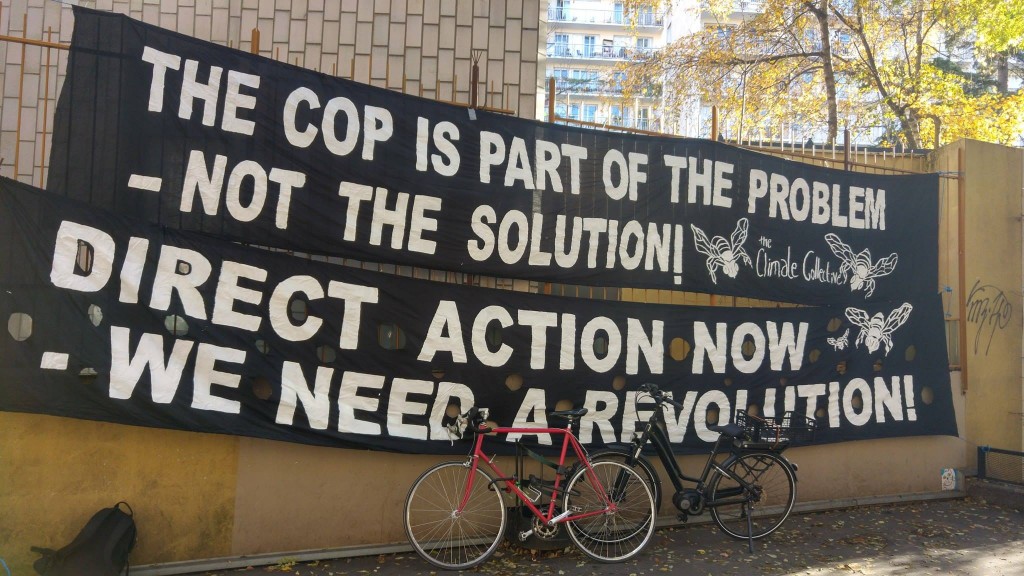

For the entire year leading up to the COP we worked on developing the Climate Games, via a series of Hackathons in art institutions (ranging from The Berliner Festspiele to The Vooruit, Ghent). These brought together artists, activists, gamers and coders to develop a web based app that would facilitate a giant game of disobedience during the COP where teams (affinity groups) would avoid Team Blue (the police) to carry out direct actions across the world against the corporate take over of the COP 21 process. An interactive map enabled teams to mark targets and document their actions and a system of prizes and awards completed this peer-to-peer disobedience game.

For the entire year leading up to the COP we worked on developing the Climate Games, via a series of Hackathons in art institutions (ranging from The Berliner Festspiele to The Vooruit, Ghent). These brought together artists, activists, gamers and coders to develop a web based app that would facilitate a giant game of disobedience during the COP where teams (affinity groups) would avoid Team Blue (the police) to carry out direct actions across the world against the corporate take over of the COP 21 process. An interactive map enabled teams to mark targets and document their actions and a system of prizes and awards completed this peer-to-peer disobedience game.

Without any central coordination, the Climate Games web site saw over 214 actions reported, involving 124 teams. There were teams that invaded car showrooms, banks and other capitalist institutions dressed as animals and vegetables leaving behind them a trail of unwanted nature. We saw disobedient bodies get in the way of some of the world's largest machines in the open cast coal mines of Germany and we heard a pirate radio station emit illegally from the top of the Eiffel tower. Thousands of fake free Parisian newspapers were distributed in the metro, whilst lobbyists offices and greenwashers got covered in good doses of paint, stinky old soup and sump oil. Rebel Clowns disrupted a live corporate TV programme that promoted false climate solutions, whilst uninvited dance parties took place in the offices of fossil fuel companies. Climbers climbed trees in the way of a new motorway, and others hung anti-nuclear banners from Paris landmarks. British fracking sites were blockaded and clandestine cycle lanes painted in Lille. Scuba divers swam through streets whilst indignant penguins protested in shopping malls, and sparkling unicorns disrupted a Christmas market. Glamorous Can Can girls welcomed punters to the Moulin Rouge with the message that we Can Can change everything, and hundreds of toilet rolls with the IPCC report printed on them were smuggled into the toilets of UN conference centre.

Without any central coordination, the Climate Games web site saw over 214 actions reported, involving 124 teams. There were teams that invaded car showrooms, banks and other capitalist institutions dressed as animals and vegetables leaving behind them a trail of unwanted nature. We saw disobedient bodies get in the way of some of the world's largest machines in the open cast coal mines of Germany and we heard a pirate radio station emit illegally from the top of the Eiffel tower. Thousands of fake free Parisian newspapers were distributed in the metro, whilst lobbyists offices and greenwashers got covered in good doses of paint, stinky old soup and sump oil. Rebel Clowns disrupted a live corporate TV programme that promoted false climate solutions, whilst uninvited dance parties took place in the offices of fossil fuel companies. Climbers climbed trees in the way of a new motorway, and others hung anti-nuclear banners from Paris landmarks. British fracking sites were blockaded and clandestine cycle lanes painted in Lille. Scuba divers swam through streets whilst indignant penguins protested in shopping malls, and sparkling unicorns disrupted a Christmas market. Glamorous Can Can girls welcomed punters to the Moulin Rouge with the message that we Can Can change everything, and hundreds of toilet rolls with the IPCC report printed on them were smuggled into the toilets of UN conference centre.

The other project we worked on was the D12 (December 12th) - Redlines action (redlines being the minimal necessities for a just and liveable planet that cannot be crossed). Working within the framework of the coalition of 150 organisations, from faith groups to unions, big NGO’s to grass roots groups, we were involved in co-designing the action (developing the concept of the red line), training people in civil disobedience and organising the action. This involved a lot of work promoting the action design and convincing the coalition to agree to support civil disobedience. Never before had such a wide variety of groups agreed to such a position during a summit mobilisation. The final red lines action was choreographed by us working with a range of activists from radical farmers unions to 350.org (http://350.org). It involved thousands of meters of red material, 5000 red tulips, 15 DIY fog horns (designed by artist Oliver Walker, 50 giant inflatable silver cobble stones (designed by art activism collective - Tools for Action), and 20,000 people refusing the ban on demonstrations. The organising and coordination of all this was done by the Labofii, working as social sculptors with all the elements.

The other project we worked on was the D12 (December 12th) - Redlines action (redlines being the minimal necessities for a just and liveable planet that cannot be crossed). Working within the framework of the coalition of 150 organisations, from faith groups to unions, big NGO’s to grass roots groups, we were involved in co-designing the action (developing the concept of the red line), training people in civil disobedience and organising the action. This involved a lot of work promoting the action design and convincing the coalition to agree to support civil disobedience. Never before had such a wide variety of groups agreed to such a position during a summit mobilisation. The final red lines action was choreographed by us working with a range of activists from radical farmers unions to 350.org (http://350.org). It involved thousands of meters of red material, 5000 red tulips, 15 DIY fog horns (designed by artist Oliver Walker, 50 giant inflatable silver cobble stones (designed by art activism collective - Tools for Action), and 20,000 people refusing the ban on demonstrations. The organising and coordination of all this was done by the Labofii, working as social sculptors with all the elements.

2. What did you or your organization/collective accomplish during COP21? And how do you measure the success of that accomplishment?

The Climate Games was one of the highlights of the COP for a lot of grassroots activists, as it enabled them to have a framework in which they could autonomously take action whilst feeling part of a wider event. The novelty aspect and the embedded humour with the awards etc. were elements that attracted people to the form. The final awards ceremony, attended by 600 people, provided a moment of collective celebration, which was both a powerful way to share the documentation of each others’ actions and a cathartic moment that was needed following the stress and difficulties of working under the state of emergency declared by France following the attacks in November 2015.

Despite never writing a single press release, the Games had excellent media coverage. They were featured in dozens of national news papers, from the UK's The Guardian to Turkey's BirGün, France’s Libération to Germany's TAZ. There were articles in diverse magazines from makers bible Makery to art historian journals and even right wing blogs claiming we were 'creepy'. Gamers were interviewed on national French radio and pirate stations several times, and the trailer was shown in cinemas and on popular web-based TV stations such as Mediapart.

Naomi Klein loved the slogan We are Nature Defending Itself—created for Climate Games—so much that she used it in several of her speeches in Paris and stuck the Climate Games sticker on her laptop. It was chanted on the streets on D12, written with beautiful moss graffiti on the walls, taken up in many actions since, and has become a bit of a meme.

The code for the Climate Games is now available as open source and several other collectives are now organising new climate games in their regions—in the UK with Reclaim the Power (grass roots climate justice movement), in Belgium with the TTIP games (opposing the Trans Atlantic Trade Agreement), and possibly in France with a Loi du travail games (against a new labour law that has given rise to a large diverse movement recently).

The gamification aspect of the Climate Games has also had an influence on the radical French movements: in Feb 2016 a carnivalesque action with teams and rules being held in support of the movement against the building of the Airport of Notre Dames des Landes took place in Rennes. In the past such movements would have tended to have a fairly narrow palette of action forms and were suspicious of less ‘serious’ approaches to resistance. Encouraging creativity and an imaginative approaches to direct action is for us at the Labofii one of the key aims of our work and so we think that the Climate Games managed to push the envelope of what is possible and modelled effective forms of beautiful trouble that have had a long lasting influence beyond COP21.

The redlines success was that we managed to normalise civil disobedience with groups that would never normally support such actions and create an action where people felt that they were ‘disobeying’ and yet felt safe enough from the threat of sever repression and the generalised fear that suffused the organising and the city of Paris after the attacks. Many activists that we have met since felt say that as a ‘gateway’ form, for new activists, it was exactly the right type of action, and many have returned home filled with enthusiasm and have begun organising locally. The redline itself has also become a meme in the climate justice movement and is being used around the world.

3. How did you respond to the limitations put in place by the French government during the “state of emergency”? How did these limitations affect the actions you took part in or planned?

In 25 years of activism I (John Jordan) have never worked in such difficult circumstances. The state of emergency forced us to rework all our plans for the redlines action, as it banned all demonstrations, and even though our aim was never to ask for permission, we had no idea what level of repression would take place in this unexpected environment. The climate of fear was palpable and many of us knew people who were affected directly by the Isis attacks, loosing relatives or being in the venues at the time. The state of emergency enabled the French government to try to host the COP without any visible forms of resistance, which was what the ministers had wanted in the first place. They clearly told us before the attacks that they would not allow anything to happen anywhere near the conference centre.

Ecological activist friends of ours were the first to be put under house arrest, and as organisers of the Climate Games who had public profiles (doing media, giving workshops, trainings, presentations) we were convinced that we would also be put under house arrest. This meant that every night we went to bed excepting our flat or office to be raided. In the end this never happened, but the stress that this put on us meant that we took decisions that were perhaps more motivated by fear than by careful political strategy. This affected the design of the redlines action more than the Climate Games though, as the decentralised nature of the games and the fact that it was merely an action framework, meant that we had no capacity to influence their form. Either we cancel or keep going. In the end we wrote a statement about why we thought that the real state of emergency was the climate breakdown, and that the games would continue.

Ecological activist friends of ours were the first to be put under house arrest, and as organisers of the Climate Games who had public profiles (doing media, giving workshops, trainings, presentations) we were convinced that we would also be put under house arrest. This meant that every night we went to bed excepting our flat or office to be raided. In the end this never happened, but the stress that this put on us meant that we took decisions that were perhaps more motivated by fear than by careful political strategy. This affected the design of the redlines action more than the Climate Games though, as the decentralised nature of the games and the fact that it was merely an action framework, meant that we had no capacity to influence their form. Either we cancel or keep going. In the end we wrote a statement about why we thought that the real state of emergency was the climate breakdown, and that the games would continue.

The redlines action totally changed. From being planned as a blockade encircling the conference centre, aiming to create a scene of social conflict at the very moment the agreement was signed, it became a much more symbolic action that took place many miles from the conference centre, near the Arc de Triomphe. We were forced to meet with the government who wanted no demonstration in any outdoor space. We negotiated hard, telling them what form the action was going to take and making very few compromises. In the end, on the eve of Dec 12th, the government “authorised” the action.

In the end I feel that we could have pushed harder and risked more, and possibly kept the original location of the conference centre, but the stress and total exhaustion of redesigning over a year’s work in 4 weeks and the fact that many of the bigger organisations in the coalition simply ran away from the disobedience after the state of emergency was declared, meant that all those organising were unable to do so. But the most powerful thing about the state of emergency is that it put the cops in our head and presented us with a situation which was like organising in an unknown land, filled with uncertainty and fear as to how the state would react.

4. What was the goal of art activism during the COP21? What role might it play in the broader context of the growing prevalence of government-imposed “states of emergency” during key times of convergence?

For the Labofii art activism at the COP21 served to: 1) Bring people new to activism into activism through forms that are inspirational, pleasurable, and that don’t look or feel like tired old demonstrations; 2) Create synergies between artists and activists by embedding artists into social movements and encouraging activists to use more creative ways of thinking; 3) Encourage a culture of resistance, where more mainstream cultural institutions support radical forms of action (the role of the hackathons being held in institutions); and 4) Create effective forms of action, effective for being unexpected and resistant to criminalisation and repression.

We will certainly see more states of emergency, as the effects of the “perfect" storm of economic, ecological and social collapse are felt. In such circumstances art can be a great shield against repression. This has been seen historically from the Orange Alternatives Gnome actions during the military dictatorship in Poland to the rituals of the Mothers of the Disappeared during the Argentine Junta. The strategy of putting one’s opponent in a position of dilemma—if they do nothing the action succeeds, if they repress they may look ridiculous and their violence backfire—is key for this. With increasing repression of resistance, art activism is going to be increasingly common as a tool to keep reinventing forms and wrong-foot the enemy, the state and capital.

5. What alliances did you build? And were any across divisions of race, class, and gender? Did you form alliances with NGOs, Indigenous activists, or other organizations beyond your own?

We think that art activism has to be imbedded in the movements, otherwise it remains an elitists cultural activity separate from the world - often a way of pretending to do politics in the art world rather than really practicing the art of activism. For the Labofii the movements are both material and the rich soil for art activism. All our organising during the COP21 involved alliances between a large network ranging from Peasant movements of La Via Campesina to the global 350.org network, Big green NGO’s such as Greenpeace and grassroots anticapitalist networks such as Climate Justice Action, the Global trade union confederations to local anarchist groups. As artists its much easier to make alliances and work with groups that would not normally open up to more radical ecological and social perspectives. Art in this way acts as a kind of bridge that opens space and potentiality rather than closes it down due to perceived ideological differences.

6. What are the lessons of COP21, and where do we go from here?

The COP was a farce, a giant greenwashing machine that will have little effect on the root causes of the climate breakdown, but at least it set a global framework, a tool - e.g keeping warming under 1.5 degrees — that we can use in our actions to highlight the fact that despite the agreement no countries or corporations are doing what is necessary to stop the climate break down from making this planet inhospitable to human life over the next century. A good article in ROAR magazine that writes about the lessons learned at cop21 from art activist organiser Kevin Buckland can be found here. He especially speaks of the work with indigenous groups and the importance of decolonising our struggle for climate justice...

The lessons that we at the Labofii gained were: 1) To return to local organising and frontline struggles and use the cop21 as a leverage - in our case this means moving to the ZAD (zone à défendre) where a project against a new airport has been resisted, and setting up a Centre for Creative Resistance there. Fight for the land you love is the lesson!; 2) The attacks in Paris foreshadowed the volatile world that we will have to deal with over the next decades - it was clear in Paris that the smaller, decentralised, autonomous groups working in networks were much better at adapting to the shock than the big organisations and NGO’s. Keep small and connected is the lesson!; and 3) And last but not least - when we feel fear, either in the face of state repression (which if our actions are successful is going to be inevitable) or in the face of the ecological breakdown (something that in our life times is likely to get worse until it is stopped!) we must try to balance the capacity to feel with the necessity to act. Fear tends towards profound paralysis and to not fear is dangerous and yet to shut out such emotions is a step towards movements that are more like machines (which tend towards authoritarianism) than the rich sensible ecosystems that inspire us. The best way to deal with such fears is to share and face them together, working with tools that mean that emotions are a key part of organising and making and not just a side issue that is dealt with occasionally. (see this fabulous essay on how to overcome the age of anxiety ). Balance on the tightrope between not feeling enough and feeling too much, this is the lesson !

The lessons that we at the Labofii gained were: 1) To return to local organising and frontline struggles and use the cop21 as a leverage - in our case this means moving to the ZAD (zone à défendre) where a project against a new airport has been resisted, and setting up a Centre for Creative Resistance there. Fight for the land you love is the lesson!; 2) The attacks in Paris foreshadowed the volatile world that we will have to deal with over the next decades - it was clear in Paris that the smaller, decentralised, autonomous groups working in networks were much better at adapting to the shock than the big organisations and NGO’s. Keep small and connected is the lesson!; and 3) And last but not least - when we feel fear, either in the face of state repression (which if our actions are successful is going to be inevitable) or in the face of the ecological breakdown (something that in our life times is likely to get worse until it is stopped!) we must try to balance the capacity to feel with the necessity to act. Fear tends towards profound paralysis and to not fear is dangerous and yet to shut out such emotions is a step towards movements that are more like machines (which tend towards authoritarianism) than the rich sensible ecosystems that inspire us. The best way to deal with such fears is to share and face them together, working with tools that mean that emotions are a key part of organising and making and not just a side issue that is dealt with occasionally. (see this fabulous essay on how to overcome the age of anxiety ). Balance on the tightrope between not feeling enough and feeling too much, this is the lesson !